News

Creative designers mix architecture with art

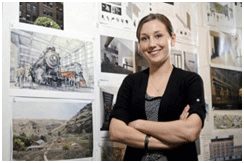

Dawn Carlton, a design staff member with Hennebery Eddy Architects, won an award from the American Society of Architectural Illustrators for a watercolor rendering of the Oregon Rail Heritage Foundation's new engine house, at left. (Photo by Sam Tenney/DJC)

There’s no question that creating buildings requires creativity, but ask professionals where they draw the line between art and architecture, and the answers are as mixed as the mediums.

“Art is for yourself, or about trying to express an idea and the purity of that idea,” said Lucas Posada, a designer atGBD Architects. “But I think design really is more about solving a problem and very rarely is it a problem for yourself – it’s a problem for a client.”

Increasingly, that problem-solving process involves the conceptual world. Whether through watercolors, physical models or 3-D building information modeling systems, Portland’s buildings are taking creative forms before becoming concrete and steel.

For Posada, architecture is the bridge between art and science, concept and calculation. He said the process is a combination of many mediums coming together to tell a story, from the graphic design in preliminary renderings to photographs of a finished facade.

“And then you need to work with good writers who help you express your ideas through the written word,” Posada said.

For Dawn Carlton, an architect at Hennebery Eddy Architects who specializes in watercolor renderings, art is an avenue for the expansion of architectural ideas.

“I use it for process studies and early design work, as a medium to explore ways of presenting and looking at the project,” she said.

Carlton recently won an award from the American Society of Architectural Illustrators for a watercolor rendering she painted of the Oregon Rail Heritage Foundation’s new engine house. Through shades of gray, green and blue, the rendering focuses on two large locomotives and a handful of visitors. ASAI will feature the painting in an exhibit in Baltimore in October.

Newlands and Co. specializes in photo realism in its architectural renderings, including one for Ankrom Moisan Associated Architects' design of the Mirabella building, at left. (Rendering by Newlands and Co.)

But technology now has the industry’s full attention.

“What’s kind of wild right now is that we’re finally seeing a full shift to 3-D design tools in architecture that has been long in coming; where instead of drafting, architectural designers are really truly modeling their spaces as they design,” said Donald Newlands of Newlands and Co. in Portland. “It’s a complete shift of tools and thinking.”

Newlands’ company specializes in creating “photo-real” virtual renderings of architectural projects. His initial interest in mapping the contextual design of sculptures grew into a passion for larger, built structures.

Over the course of its 24-year history, the company has developed a complete, working 3-D model of the entire Portland area. It’s visible on KGW’s nightly weather report.

“It looks like a helicopter photo,” Newlands said. “You probably wouldn’t know you’re looking at a 3-D model.”

Newlands said the introduction of BIM systems and software like Google’s SketchUp – an easy-to-use 3-D design tool – have completely changed not only how an idea is developed, but how it is sold.

Over the years, Newlands and Co. has developed a working 3-D model of the entire Portland area. (Rendering by Newlands and Co.)

“We can create a photo-perfect world with everything exactly the way we want to, and set the light the way we want to, and the sky the way we want to, and populate it the way we want to, and create the environment in a way that stages clients’ projects exactly the way they want them staged,” he said.

Newlands and Co., for example, created renderings for Ankrom Moisan Associated Architects’ design of the Mirabella building in the South Waterfront District. The renderings’ details extend to reflections of trees in the building’s windows.

But Newlands said sometimes a project needs a more stylized approach. The company recently created renderings for a road project that used more of a cartoon-like signature.

“We came up with something that I think was sort of beautiful but didn’t beg the issues that hadn’t been designed yet, which is a real issue with photo realism,” Newlands said.

Certainly, traditional design methods still hold appeal.

“I think hand work in general is so important to architectural design,” Carlton said. “Technology has moved so far forward that most work is done on the computer. I think any chance that we get as designers to go back to hand work, whether that’s pencil or mixed media, there’s a real connection level of thought process that that supports.”

Carlton, who has painted with watercolors most of her life, said the medium lets her focus on the intent of a space rather than its dimensions.

“I think the softness is also appealing to a lot of clients, versus say a black-and-white image or other opaque paintings that make it difficult to express the detail,” she said.

Brent Linden, a senior associate at Allied Works Architecture and a past visiting professor at the University of Oregon, also believes in using art to explore a building’s purpose.

The company, founded in 1994, is known for its abstract physical models that often bear little resemblance to the eventual buildings. Linden described a model of the Clyfford Still Museum in Denver that featured a solid, wooden beam of Douglas fir with mini pylons and cubed spaces carved into it.

“And so taking this physically solid thing and then having one act, which is the act of biting into it with a router that makes both spaces – both the landscaped space and the interior space – is for us both an exploration and a communication of the fact that it’s one experience,” Linden said.

The model could seemingly fit in someone’s living room, but Linden declined to say whether it should be considered a piece of art or a tool.

“I’ve been there for 10 years and have been through numerous processes of working with these things, and I don’t know that I’m qualified to call any of the work we do art,” he said, “mostly because that’s an open question for me about what even art is and what act can be described as art or not.”

- Cover Story

-

SketchUp Can Help You Win Interior..

SketchUp Can Help You Win Interior.. -

Best Laptops for SketchUp

Best Laptops for SketchUp -

How to Resize Textures and Materials..

How to Resize Textures and Materials.. -

Discovering SketchUp 2020

Discovering SketchUp 2020 -

Line Rendering with SketchUp and VRay

Line Rendering with SketchUp and VRay -

Pushing The Boundary with architectural

Pushing The Boundary with architectural -

Trimble Visiting Professionals Program

Trimble Visiting Professionals Program -

Diagonal Tile Planning in SketchUp

Diagonal Tile Planning in SketchUp -

Highlights of some amazing 3D Printed

Highlights of some amazing 3D Printed -

Review of a new SketchUp Guide

Review of a new SketchUp Guide

- Sketchup Resources

-

SKP for iphone/ipad

SKP for iphone/ipad -

SKP for terrain modeling

SKP for terrain modeling -

Pool Water In Vray Sketchup

Pool Water In Vray Sketchup -

Rendering Optimization In Vray Sketchup

Rendering Optimization In Vray Sketchup -

Background Modification In sketchup

Background Modification In sketchup -

Grass Making with sketchup fur plugin

Grass Making with sketchup fur plugin -

Landscape designing in Sketchup

Landscape designing in Sketchup -

Apply styles with sketchup

Apply styles with sketchup -

Bedroom Making with sketchup

Bedroom Making with sketchup -

Review of Rendering Software

Review of Rendering Software -

Enhancing rendering for 3d modeling

Enhancing rendering for 3d modeling -

The combination of sketchup

The combination of sketchup -

Exterior Night Scene rendering with vray

Exterior Night Scene rendering with vray